Frontotemporal dementia: What is it?

In the United States alone, approximately 50,000 to 60,000 have frontotemporal dementia. This early onset form of dementia is devastating to the brain and body as language skills decrease and the muscles become immobile. Continue reading to learn more about how frontotemporal dementia.

What is Frontotemporal Dementia?

Frontotemporal dementia is a group of nervous system disorders that result from damage to the cells (neurons) in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. As brain matter in those areas atrophy, it affects behavior, personality, language, and motor movement. Memory remains stable as other cognitive skills progressively decline.

Compared to other forms of dementia such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, frontotemporal dementia has an earlier age of onset. Approximately 60 percent of patients range from 45 to 64 years old.

Types of Frontotemporal Dementia

Many individuals with frontotemporal dementia differ in presentation. No two patients are identical. This is because are multiple types of frontotemporal dementia that are further categorized by specific variants.

Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia

The behavioral variant is the most common. It presents very similar to Alzheimer’s dementia, but with memory intact. The behavioral variant is characterized by drastic changes in behavior and personality. Over time, the induvial loses the ability to discern appropriate social behavior. They become apathetic, lack self-control, and have little awareness for their behavior.

Primary Progressive Aphagia

Primary progressive aphagia is a type of frontotemporal dementia that impacts language skills. This includes speaking, writing, and comprehension. Language skills and speech gradually become impaired. The issue with language is initially the only symptom. While primary progressive aphagia typically develops in midlife, the disorder can present after age 65.

There are three variants of primary progressive aphagia. The semantic variant occurs when the individual experiences a progressive loss of meaning of words. They are able to speak and speaking typically remains fluent, yet spoken words are difficult to understand. If the person presents with delayed, ungrammatical speaking, they likely have the aggramatic variant. In cases of the logopenic variant, grammar is unaffected but the person has difficulty retrieving words during a conversation.

Movement Disorders

Certain movement disorders are connected to frontotemporal dementia because they affect language abilities. Some patients have corticobasal syndrome due to a loss of nerve cells in the cerebral cortex and the basal ganglia. Motor symptoms like apraxia are the main manifestation, especially the inability to use the hands or arms that begins on one side of the body. A subset of these patients develop language and cognitive delays first. A second movement disorder is known as progressive supranuclear palsy. It interferes with balance, walking, and facial expressions. Symptoms are upper body stiffness, problems with eye movements, and eventually, cognitive symptoms (e.g. poor memory, judgment, and behavior).

Symptoms of Frontotemporal Dementia

The symptoms of frontotemporal dementia impact behavior, personality, language, and physical body movements. They progressively worsen over time. Physical symptoms and memory loss tends to appear later in the disease process.

- Apathy

- Behavior and Personality Changes (e.g. mood swings, theft, increased interest in sex, poor personal hygiene)

- Cognitive Decline

- Compulsive Behaviors (e.g. collecting objects, drinking alcohol, etc.)

- Decreased Self-Awareness

- Depression

- Dysphagia (Trouble Swallowing)

- Emotional Withdrawal

- Fatigue

- Incoherent Speech

- Inability to Pronounce Words

- Lack of Empathy

- Loss of Mobility

- Memory Loss (late stage only)

- Misunderstanding Speech

- Muscle Weakness, Twitching, Stiffness, and Rigidity

- No Motivation

- Overeating and Weight Gain

- Poor Judgment, Planning, and Organization

- Repetitive Speech

- Socially inappropriate, impulsive, or repetitive behaviors

- Speaking Slowly

- Using Words Incorrectly

Early Signs of Frontotemporal Dementia

In the early stages of frontotemporal dementia, physicians may confuse the disorder with other forms of dementia or mental illness. Individuals undergo drastic behavioral and personality changes. They behave impulsively, often making decisions that are inappropriate, careless, or even criminal. As they lose the ability to judge social norms, they have little interests in hobbies and self-care. They may disregard the feelings of others and act unusually cold toward others.

Late Stage of Frontotemporal Dementia

Later stages of frontotemporal dementia manifest with physical rather than behavioral symptoms. As the brain damage progresses, patients are likely to develop movement disorders which includes muscle weakness, rigidity, difficulty swallowing, and twitches. They fail to make motor responses after verbal commands. Eventually, most become mute. If memory loss does occur, it happens in the late stage. Those in late stages struggle to complete daily tasks (e.g. walking and eating) without assistance.

Causes of Frontotemporal Dementia

The incidence of frontotemporal dementia is equal amongst men and women. Having a family member with the disorder increasing its chances of development in the future. Experts have identified several genes that cause frontotemporal dementia, indicating it is a genetic condition.

Mutations in the tau gene result in the protein to form tangles with the neurons in the brain, which leads to the death of brain cells. The GRN gene is also seen in frontotemporal dementia patients, as mutations decrease the production of progranulin. Consequently, TDP-43, another protein, is defective in the brain. The most common genetic mutation in those with frontotemporal dementia is in the gene C9ORF72. Individuals with this mutation are susceptible to both frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Brain Characteristics in Frontotemporal Dementia

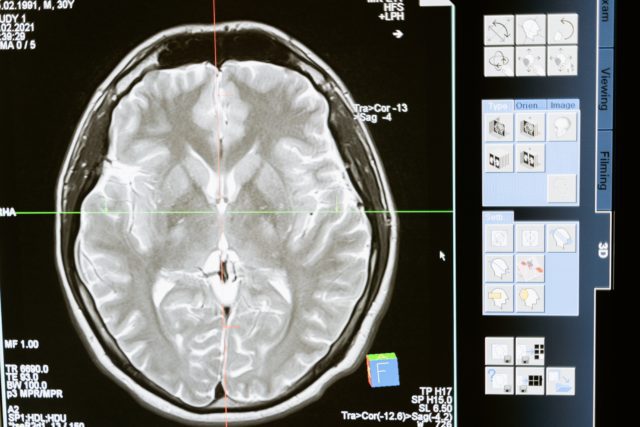

Frontotemporal dementia undoubtedly has a range of psychological, behavioral, and emotional symptoms. These neurological symptoms affect the brain and are evident through brain imaging like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tracer (FDG-PET) scan. Firstly, gray matter atrophy is apparent on scans. Experts can determine the subtype of frontotemporal dementia by visualizing these patterns of atrophy. Brain scans can also measure metabolic factors in the brain. Studies revealed that patients with decreased metabolism in the left anterior temporal lobe have the semantic variant of frontotemporal dementia (Whitwell, 2012).

Diagnosing Frontotemporal Dementia

A thorough medical history is crucial to diagnosing frontotemporal dementia to identify possible medical problems that could be causing symptoms. Blood tests to evaluate kidney and liver disease are the beginning diagnostic steps. Brain imaging is crucial to rule out structural causes for the patients symptoms such as a tumor, a stroke, or hydrocephalus. Scans also measure brain metabolism. Lower levels of metabolism in certain areas of the brain are indicative of dementia. Genetic sequencing has recently become a useful diagnostic tool. It identifies mutation in the genes that are connected to the development of the disorder.

Differentiating Frontotemporal Dementia from Alzheimer’s Dementia

Although both classified as dementia, frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia are two different diagnoses. Frontotemporal dementia is diagnosed between ages 40 and 60, memory loss is not evident until later stages, and behavioral changes occur at onset. Alzheimer’s dementia is diagnosed later in life, has memory loss as an initial symptom, and alterations in behavior develop as the condition progresses. Those with Alzheimer’s exhibit poor word retrieval—forgetting names and words—but their speech is not incoherent like in frontotemporal dementia.

Prognosis of Frontotemporal Dementia

The prognosis of frontotemporal dementia is poor. The disease is always progressive, but the rate in which symptoms worsen is variable. The average life expectancy is 8 to 10 years after the diagnosis. However, some patients can survive longer or pass more quickly.

Frontotemporal Dementia Treatment

Frontotemporal dementia has no cure. Treatment focuses on symptoms management through therapy, medications, and support from loved ones.

Therapy

Experts recommend those with frontotemporal dementia have speech therapy. This helps with swallowing difficulties, as well as speaking coherently. Additionally, many patients with frontotemporal dementia lose the ability to care for themselves. Occupational therapy teaches the patient coping skills and provides them with the tools to be independent in daily tasks such as getting dressed, self-care, and work. Physical therapy creates a personalized exercise plan to increase the patient’s mobility and muscle weakness.

Medication

Unfortunately, there are few medication options to treat frontotemporal dementia. Antidepressant medications targeting neurotransmitters in the brain like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) treat secondary depression and mood disorders. Medications used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease that increase the amount of dopamine available to the brain are effective in some cases, especially for cognitive symptoms.

Tips For Living with Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal dementia is a challenging condition to live with. The diagnosis depends regular medical care from a variety of specialists. Patients must rely on continual care from a loved one or a 24-hour facility to assist them with daily tasks and self-care. It is advised that patients and caregivers follow a consistent routine. Both need outlets to express their emotions regarding the disorder. While the patient with frontotemporal dementia probably displays less interest in activities they once enjoyed, it is imperative to ensure they still participate in stimulating activities that will train their cognitive skills.

References

Bruun, M., Koikkalainen, J., Rhodius-Meester, H., Baroni, M., Gjerum, L., van Gils, M., Soininen, H., Remes, A. M., Hartikainen, P., Waldemar, G., Mecocci, P., Barkhof, F., Pijnenburg, Y., van der Flier, W. M., Hasselbalch, S. G., Lötjönen, J., & Frederiksen, K. S. (2019). Detecting frontotemporal dementia syndromes using MRI biomarkers. NeuroImage. Clinical, 22, 101711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101711

Jicha, G. A., & Nelson, P. T. (2011). Management of frontotemporal dementia: targeting symptom management in such a heterogeneous disease requires a wide range of therapeutic options. Neurodegenerative disease management, 1(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.2217/nmt.11.9

Whitwell, J. L., & Josephs, K. A. (2012). Recent advances in the imaging of frontotemporal dementia. Current neurology and neuroscience reports, 12(6), 715–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-012-0317-0

Cheyanne is currently studying psychology at North Greenville University. As an avid patient advocate living with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome, she is interested in the biological processes that connect physical illness and mental health. In her spare time, she enjoys immersing herself in a good book, creating for her Etsy shop, or writing for her own blog.